In a previous essay, I wrote about Bias as being a Tale of Two Systems, one of which thinks fast and one of which thinks slow. System 1 forms “first impressions” and often is the reason why we jump to conclusions. This is the Thinking Fast system. System 2 is the analytical, “critical thinking” way of making decisions. System 2 does reflection, problem-solving, and analysis. This is the Thinking Slow system.

At the end of this first essay, I noted that I would be reviewing a number of biases over a series of articles. This is the first of those subsequent articles in which we will be addressing illusory (or spurious) correlations as a common form of bias.

An illusory or spurious correlation is the phenomenon of perceiving a relationship between variables (typically people, events, or behaviors) even when no such relationship exists. A false association may be formed because rare or novel occurrences are more salient and therefore tend to capture one’s attention. This phenomenon is one way stereotypes form and endure.

Illusory correlations occur in part due to WYSIATTI thinking (What You See Is All That There Is).

There is a great website called Spurious Correlations that allows you to look up thousands of variables to create your own illusory (or spurious) correlations. https://www.tylervigen.com/spurious-correlations For example, I bet you didn’t know the following:

*As the per capita consumption of cheese in the United States increases, the price of PepsiCo stock also increases (.96 correlation).

*As the rate of Bachelor degrees awarded in Psychology increases, the number of vinyl album sales also increases (.90 correlation).

*The number of Google searches for “how to fake your own death” correlates .96 with the number of tax examiners, tax collectors, and revenue agents in Louisiana.

System 1 is highly adept in one form of thinking — it automatically and effortlessly identifies causal connections between events, sometimes even when the connection is spurious or not really there. This is the reason why people jump to conclusions, assume bad intentions, give in to prejudices or biases, and buy into conspiracy theories. They focus on limited available evidence and do not consider absent evidence. They invent a coherent story, causal relationships, or underlying intentions. And then their System 1 quickly forms a judgment or impression, which in turn gets quickly endorsed by System 2.

As a result of WYSIATI and System 1 thinking, people may make wrong judgments and decisions due to cognitive errors. If we had to think through every possible scenario for every possible decision, we probably wouldn’t get much done in a day. In order to make decisions quickly and economically, our brains rely on a number of cognitive shortcuts known as heuristics. These mental rules-of-thumb allow us to make judgments quite quickly and often times quite accurately, but they can also lead to fuzzy thinking and poor decisions.

As a result of WYSIATI and System 1 thinking, people may make wrong judgments and decisions due to biases and heuristics. There are several potential errors in judgment that people may make when they over-rely on System 1 thinking. Again, illusory correlations are one of the most common examples of a heuristic gone wrong.

An illusory correlation is the phenomenon of perceiving a relationship between variables (typically people, events, or behaviors) even when no such relationship exists. A false association may be formed because rare or novel occurrences are more salient and therefore tend to capture one’s attention. This phenomenon is one way stereotypes form and endure over time.

Let’s talk about a rather common example. It is common lore that a full moon impacts any number of events from hospital admissions, on call events, emergency runs, police calls, traffic accidents, etc. The reality is that study after study has found no connection between a full moon and higher incidences of unusual events. But here’s the interesting thing: Even though the research says otherwise, a 2005 study revealed that 7 out of 10 nurses still believed that a full moon led to more chaos and patients that night.

An illusory correlation happens when we mistakenly over-emphasize one event(s) and ignore others. For example, let’s say you are a nurse working in the ER during a full moon shift and you have two patients who are quite agitated and require the police to be called.

When you think back on your shift, it is easy to remember those experiences and conclude that “the weirdos come out during a full moon.” However, you are forgetting about all of the other shifts you worked during a full moon, and nothing happened (or the nights it wasn’t a full moon and things happened. There was nothing notable or salient to you on those shifts for you to remember.

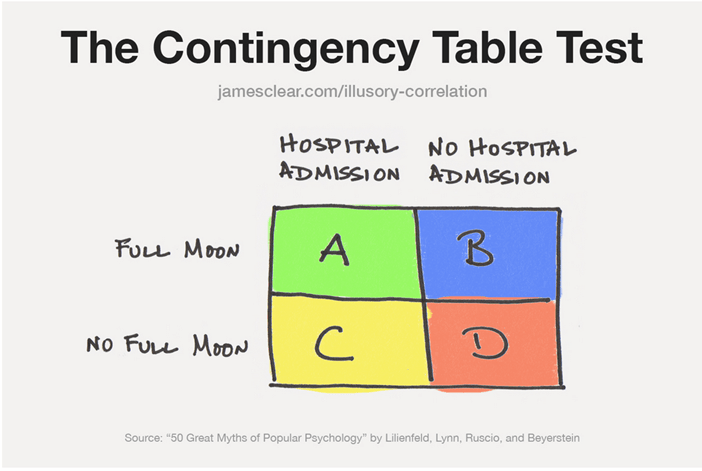

The following contingency table may help explain what is happening in nurse’s minds with regards to our full moon example. This isn’t a knock on nurses. Firefighters, police, crisis line staff all report similar beliefs with respect to full moons and its impact on their jobs.

Cell A: Full moon and a busy night. This is a very memorable combination and is over-emphasized in our memory because it is easy to recall.

Cell B: Full moon, but nothing happens. This is a non-event and is under-emphasized in our memory because nothing really happened. It is hard to remember something not happening and we tend to ignore this cell.

Cell C: No full moon, but it is a busy night. This is easy to dismiss as a “crazy day at work.”

Cell D: No full moon and a normal night. Nothing memorable happens on either end, so these events are easy to ignore as well.

This contingency table helps reveal what is happening inside the minds of nurses during a full moon. The nurses quickly remember the one time when there was a full moon and the hospital was overflowing, but simply forget the many times there was a full moon and the patient load was normal (or the times there was no full moon but hospital was busy). Because they can easily retrieve a memory about a full moon and a crazy night and so they incorrectly assume that the two events are related.

There are a few steps you can take to try and combat falling victim to an illusory correlation. They are as follows:

1. Identify the variables: The first step in combating illusory correlation is to identify the variables that are being observed. This can be done by carefully examining the data and looking for patterns that might suggest a relationship between two variables.

2. Consider alternative explanations: Once the variables have been identified, it is important to consider alternative explanations for any observed patterns. For example, just because two variables appear to be correlated does not necessarily mean that one is causing the other. It is possible that the relationship is due to some other factor that has not been considered.

3. Seek out contradictory evidence: Another way to combat illusory correlation is to seek out evidence that contradicts the perceived relationship. This can be done by looking for instances where the two variables are not correlated or by examining cases where the opposite relationship is observed.

4. Challenge stereotypes: Stereotypes are a common cause of illusory correlation, so it is important to challenge them whenever possible. This can be done by exposing people to positive examples of the group in question or by providing information that contradicts the stereotype.

5. Keep an open mind: Finally, it is important to keep an open mind when examining any perceived relationship between two variables. This means being willing to consider alternative explanations and being open to changing one’s beliefs in light of new evidence.

Leave a comment